Anselm Kiefer’s recent exhibition, Golden Age, at Hong Kong’s Villepin Gallery, brings together a series of paintings that explore the myth and reality of the utopian idea.

The past plays an integral role in German artist Anselm Kiefer’s work. Born in 1945 in Donaueschinge, Germany, not long before the end of the second world war, Kiefer grew up in a place and time when those who had survived it would rather not discuss the war. “The quasi natural reflex, engendered by feelings of shame and a wish to defy the victors, was to keep quiet and look the other way,” writes W.G. Sebald, a writer who like Kiefer also grew up in post war Germany and whose work is preoccupied with the destruction and rubble of the war. In defiance of what he experienced around him Kiefer set about creating work that confronted history, with its ugliness, shame, horror and guilt, and creating works that are a testament to the past.

Through a long process of layering materials, paint, and motifs Kiefer reworks and circles back to the same themes in his oeuvre— destruction, recreation, and the cycle of life and history. The ruins and rubble of the war served as his playground and would become a leitmotif in his work. In a way, Kiefer’s paintings are an act of remembrance, concerned with the preservation—and decay—of history and memory. Kiefer’s recent exhibition at Hong Kong’s Villepin Gallery, Golden Age, brings together a series of paintings layered with gold leaf, lead, oil, acrylic, soil, sediment, and various objects, resulting in encrusted topographical landscapes that gleam like golden religious icons. Created between 2020 and 2022, the paintings are thickly impastoed, depicting lofty mountains—a utopian metaphor— set against gold skies.

The landscapes Kiefer presents in this exhibition are, like all his paintings, devoid of people, their absence underscored by a lone bike, or an empty bucket collaged into the composition. Unlike the monumental, architectural canvases for which the artist has become known, depicting dystopian landscapes, the works in this exhibition — a series of alpine landscape paintings and one sculpture— are smaller, though no less densely layered, emphasising material and process, excavating history, and demanding attention and effort to be deciphered. They appear, at least initially, to depict a vision that is optimistic and carefree.

Copyright : © Anselm Kiefer. Photo : Georges Poncet

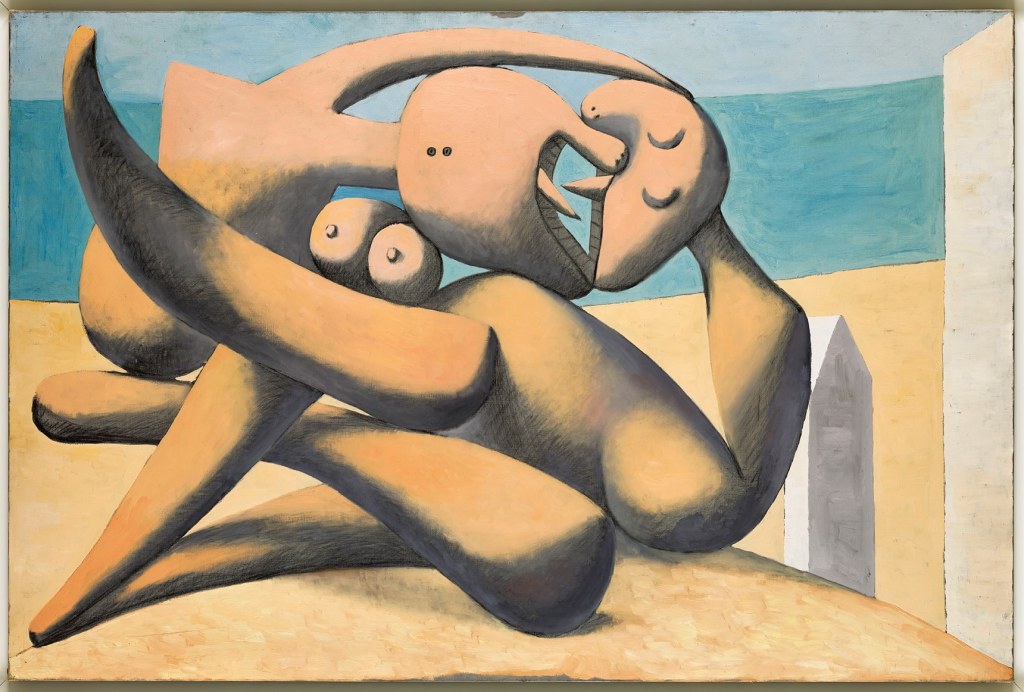

Paintings in this exhibition feature phrases in German, Italian, and Náhuatl scrawled across golden skies, mountainscapes, or thickly painted canvas bases, decoding the embedded iconography and providing crucial context. The written word threads through Kiefer’s oeuvre, with his works—including this series—deeply shaped by literature, poetry, and mythology. He draws from diverse sources like German and Norse myths, Kabbalah, alchemy, Aztec, Mesopotamian, and Roman lore to evoke the Manichean struggle that is the core of the human condition and experience. Titles borrow from literature and philosophy, while words unfurl across surfaces, underscoring the fusion of painting and poetry. ‘Brunhildes Fel’, scrawled across a painting of a large boulder encircled by autumnal leaves, draws on the Germanic and Norse legend of Valkyrie Brunhilde—Odin’s daughter and key figure in Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, which played softly during the gallery visit. ‘Teocuitlatl’ (2021–2022), a Náhuatl term for gold meaning “excrement of the gods” (or holy shit, if you will) streaks a golden canvas, evoking El Dorado’s fabled city. Yet its foreground wheat field nods to Spanish colonisation’s toll: resource plunder, land theft for agriculture, disease spread, slavery, and indigenous subjugation.

The exhibition’s title and theme draws on German philosopher and cultural critic Ernst Bloch’s writings on the Golden Age and utopia (Spirit of Utopia, 1918; The Principle of Hope, 1954). From Greek ou-topos (“no place”), utopia denotes an imaginary realm, tracing to Plato’s Republic as an ideal future. The Golden Age—an idyllic period of prosperity, peace and human civilisation—has its roots in Greek mythology, earning a mention in the works of the poet roots in Hesiod and Plato. Kiefer loops through history, blending myth and reality for a utopia that seems romantic at first glance but reveals a far grimmer vision. Beneath the impastoed layers of paint, gold leaf, and history lies Kiefer’s complex vision of the Golden Age and utopia. Contradictions, metaphors, and duality are what Kiefer has long played with in his work, and they are layered and pieced together like a puzzle in this exhibition, revealing an ironic postmodern sensibility laced with humour. He weaves tension between hope and despair, earthly and divine, chaos and order, to grapple with the world’s enigmas.

Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, straw, steel and charcoal on canvas

Copyright : © Anselm Kiefer. Photo : Georges Poncet

An unorthodox Marxist and initial supporter of the Soviet Union and Stalin—before his disillusionment—Bloch envisioned utopia as a socialist struggle, not mere escapist fantasy. Yet the 1917 Russian Revolution and socialist efforts failed to deliver worker liberation or paradise. In ‘Diamat ‘(2020–2022), named for Stalin’s codification of Marxist dialectical materialism—which posits progress through class conflict—Kiefer depicts a rickety, handlebar-less steel bicycle precariously loaded with bricks, embodying the collapse of Bloch’s hopes. Dialectical materialism underpinned the Soviet totalitarian state, but the 1989 revolutions toppled the Berlin Wall and Iron Curtain, leaving diamat’s ruins behind. Former Communist nations still grapple with its legacy. Kiefer’s bicycle wheel evokes history’s cycles, while bricks symbolise civilisation’s rubble—or here, a failed ideology—halting forward motion under the weight of the past’s debris.

A prolific writer and influential thinker, Bloch penned 1920s–1930s essays on the Weimar Republic’s ‘Golden Twenties,’ when Berlin pulsed as Europe’s avant-garde epicentre of intellectual and artistic ambition. Art and literature, he argued, would light utopia’s path—until fascism brutally intervened. In a later postscript to Heritage of Our Times (1935), Bloch reflected: “The Golden Twenties: The Nazi horror germinated in them.” The result was the destruction of hope and a shadow cast across history for decades.

Emulsion, oil, acrylic, shellac, gold leaf, straw, bucket and charcoal on canvas. Courtesy of Villepin.

The dark side of utopia, particularly when framed within political discourse, also emerges in ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’ (‘In the Early Dew to the Mountains’), a comparatively minimalist and abstract painting, the surface of which is covered in smooth gold leaf, featuring a small bike perched on the ridge of a textured black patch of mountain. The title ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’ playfully outlines the top ridge of the mountain. Originating from a 1920s German folk song adapted from a Swedish original, the painting and its accompanying song evoke an idyllic youth spent in the great outdoors, spent in the great outdoors, brimming with adventure and the redemptive power of nature. The song ‘Im Frühtau zu Berge’, also carries echoes of Germany’s Wandervogel youth movement, founded in the early 20th century. Emphasizing German nationalism, Teutonic values, and communion with nature, the group spurred a folk song revival that included this tune. By the 1930s, the Nazis co-opted it, transforming hiking into paramilitary nationalism, paving the way for the Hitler Youth (Hitlerjugend) and League of German Girls (Bund Deutscher Mädel), whose songbooks later featured the piece.

Kiefer recognizes that reactionary and revolutionary eras, like the Third Reich and the Soviet Communist Party, harnessed utopian imagery and myths for political propaganda. Utopia frequently devolves into dystopia, as philosopher Karl Popper observed in Plato’s Republic, which bore traits of totalitarianism that influenced 20th-century regimes. History proves utopia a defective social blueprint, perpetually falling short of its ideals.

Kiefer’s Golden Age offers no cloying nostalgia for a mythical past or nonexistent utopia, but a stark caution. A better world seems attainable, yet hopes often prove illusory—Ernst Bloch himself saw hope falter. The unmentionable past Kiefer confronts and the present together reveal that passive hope falls short; public imagination gets co-opted by hollow slogans and ideology. History shapes the present, and amid the “darkness of the lived moment,” wisdom can redeem humanity by learning from the past, sidestepping repeated tragedies rather than chasing idealized golden ages or utopian mirages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.