The first time I remember encountering Patricia Piccinini’s work was in 1999. A huge photograph of a beautiful woman with a rat on her shoulder was splashed across a high rise building in Melbourne’s CBD, like a slick billboard advertisement. The rat had a human ear growing on its body; it’s one of those images that gets seared into your memory.

Titled ‘Protein Lattice’ (1997), the digitally manipulated photograph was part of a series inspired by the 1997 genetic engineering experiment by Harvard surgeons and an MIT engineer, known as Vacanti mouse, in which a laboratory mouse had what looked like a human ear grown from its body. Although the ear grown from the mouse’s body was in fact cultivated from bovine cartilage cells for the purpose of plastic surgery, the controversial experiment signalled a transgression of the human/animal boundary, and would change the world of science.

In the almost three decades since producing that series, Piccinini has gone on to exhibit internationally in institutions, museums and biennales, including as Australia’s representative at the 2003 Venice Biennale. In June of this year, Piccinini opened HOPE, her first in-depth survey in Hong Kong. The immersive exhibition at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun Contemporary art space features over 50 works including hyper-realistic sculptures, paintings and moving images, that explore the frontiers of biotechnological intervention, blur the relationship between the natural and the artificial, and engage with the politics of identity, difference and diversity.

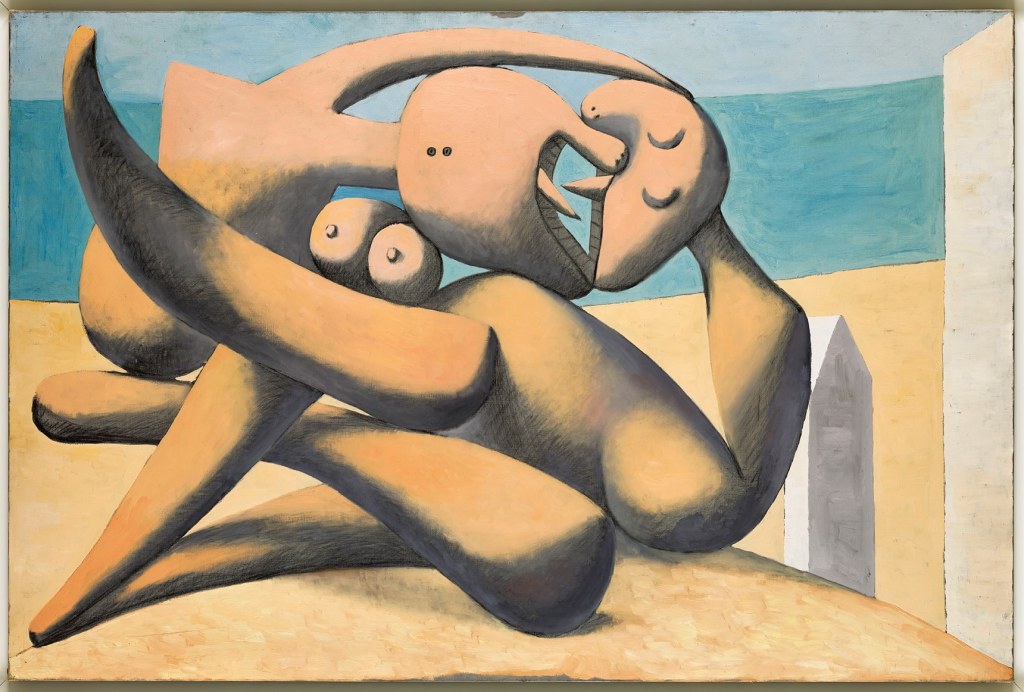

Although Piccinini’s work seems steeped in science fiction, it very much engages with 21st century issues, raising questions about progress — its impact on humans, animals and the environment—and the ethics of biotechnology. With the possibility of technological intervention, what can the future human body look like? Will we be able to love and accept these scientifically and technologically altered bodies and creations? With pollution and the climate crisis exacerbating, how will that impact animal species we share the planet with? Underlying Piccinini’s work is an experimentation with and exploration of posthumanism, a theory that sees human evolution enmeshed with the environment and technology.

In examining the posthuman condition Piccinini explores the way in which scientific and technological progress has changed our relationship with the subject and the body, questioning representations of the posthuman body, and the idea of socially acceptable body types. Today, the human body can be modified, and DNA can be manipulated or engineered, through gene editing like CRISPR or cloning. As posthuman subjects there is the capacity for technological mediation to an unprecedented degree, leading to a redefinition of human bodies and identities, and a reassessment of the ‘self’ and the ‘other’.

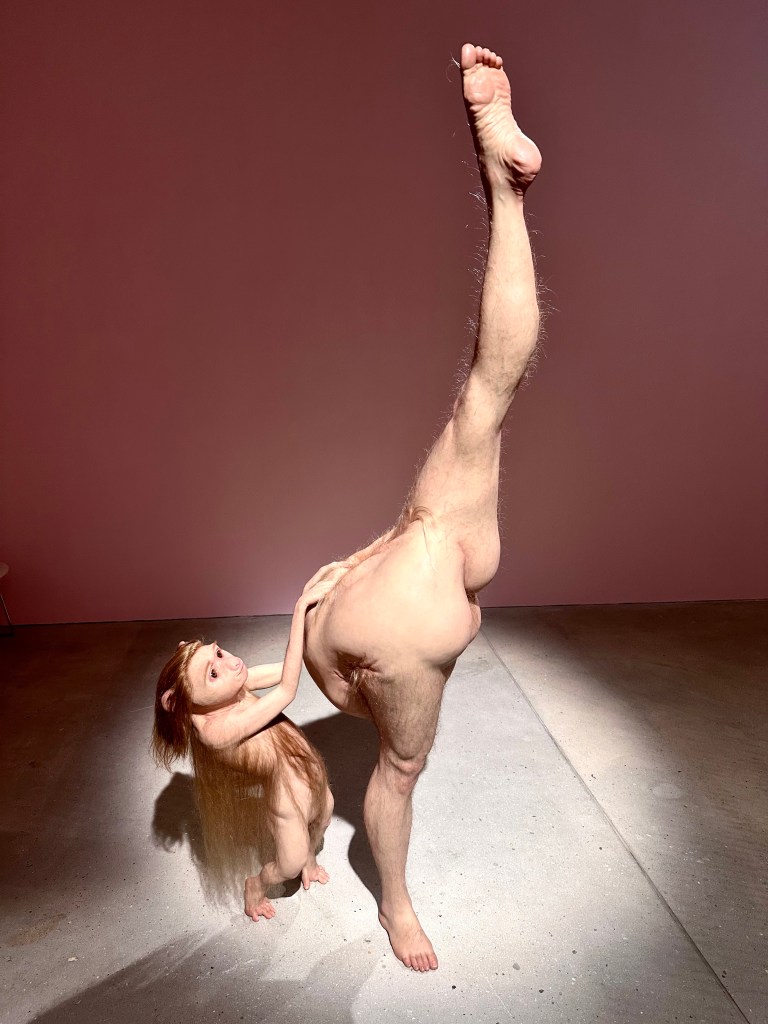

Dotted around the expansive exhibition space are hyper-realistic, animal-human hybrid sculptures made from silicone, fibreglass and human hair. They are frozen in mundane activities and poses: lying in bed in an embrace, cuddling infants, holding a bird, clambering atop a precarious tower of chairs. These creatures are resolutely ‘other’, with porcine ears or bat-like nose, webbed feet or a tail—a fusion of human, animal and even objects, like shoes— but their folds of skin, moles, skin pores, wrinkles and bodily hair are also very familiar to us, very human, and provoke a range of ambivalent and complex reactions from visitors, from revulsion, pity, and anxiety, to sympathy, curiosity and affection.

Contemporary posthuman philosopher, Rosi Braidotti, argues that “The posthuman is usually met with anxiety about the excesses of technological intervention and the threat of climate change. Or by the elation about the potential for human enhancement.” These polar reactions highlight the paradoxes and tensions of our era, between “finding alternative modes of political and ethical agency to deal with our technologically mediated world, and the fear and inertia of established norms of thinking and habits,” Braidotti continues. Within these uncanny works we confront the porous boundaries between animal and human, and we are forced to re-evaluate what is human. They capture the complexity of attempting to empathize with bodies that are vastly different from our own, and our ability (or lack thereof) to identify with other bodies, whether human, non-human, animal or virtual.

Several of Piccinini’s creations blur the lines so completely between what was/is human and the ‘other’, that it is not entirely clear where the human ends and the ‘other’ begins, thus challenging our relationship to the ‘other’. Works like the phallic looking flesh forms and orifices of ‘Atlas’ and ‘Sphinx’, and the headless statuesque creature, ‘The Pollinator’ — balletic limbs with a fleshy growth hidden in a marsupial-like pouch — trigger revulsion, a consequence of confrontation with the abject. As French philosopher, Julia Kristeva, explains in The Powers of Horror: An Essay of Abjection (1980), the abject occurs when the human reacts — with horror or a feeling of nausea — to a threatened breakdown in meaning caused by the loss of the distinction between subject and object or between ‘self’ and ‘other’. With their dismembered and deformed parts taken from the human body or made from human stem cells, Piccinini’s creatures violate the integrity of the human species.

However, Piccinini’s creatures are also strangely likeable — they may look monstrous, but they do not behave as such. The hybrid creatures come across as fragile, vulnerable, curious and nurturing. They have peaceful, kindly, countenances, and are caring and interdependent, such as in ‘The Loafers’ in which two cute, tiny, infant figures are joined together, resting against one another. The bond and love the creatures demonstrate for each other makes them relatable and elicit empathy from the viewer. There is a sentimentality to these creatures, divorced from the more violent, aggressive and unpleasant aspects of nature.

To arouse viewer empathy, Piccinini often invokes the maternal with her hybrid creations. Many have features and qualities that are attributed to the female. In the sculpture ‘No Fear of Depths’ (2019) an Australian humpback dolphin/humanoid hybrid cradles a young human girl (modelled on Piccinini’s own daughter). It is a portrait of interspecies tenderness, mothering, nurturing and empathy that crosses biological lines.

Similarly, ‘Kindred ‘(2018) depicts a simian-looking mother with two infants clutching to her, while ‘The Bond’ (2016) features a human mother holding a hybrid child whose back resembles the sole of a shoe. In ‘The Young Family’ (2002), a porcine looking mother lies on her side, suckling a litter of four offspring. She looks on as her youngsters feed and play, looking tired, defeated and a little anxious.

Nurture, of course, is not the preserve of one gender alone — it is about relationships not biology. ‘Eagle Egg Man’ (2018) challenges human gender stereotypes about care-giving as a trio of male creatures cradle their pouches full of fragile eggs. Piccinini reminds us that life is not the exclusive property or right of one species over all others, and that love is not the exclusive set of emotions and behaviours of humankind — non-human creatures also lead complex lives with social bonds and community.

Piccinini’s work suggests that with creation, be it through procreation or genetic engineering alike, we have a moral responsibility to care for the result. In ‘The Couple’ (2028) the artist reverses the Frankenstein narrative. Unlike Dr Victor Frankenstein, Piccinini nurtures her monstrous creations. As mother/creator she does not abandon her monster, alone in the world, instead, she gives it a partner, and a home. The monstrous-looking couple cuddle together in bed, the trappings of domesticity around them, and a foundling child (‘Foundling’, 2008) —a wrinkled, large-eyed, new-born baby/creature (perhaps an unwanted product of genetic engineering) — lies in its bassinet close by.

The exhibition invites visitors to reflect on what it means to be human, but also the role humankind has played in the unprecedented suffering of animals through scientific experimentation, exploitative factory farming and climate change, and the cognitive dissonance that has resulted from our harmful actions. ‘Cleaner’ (2019), a sculpture of a turtle with a plastic yellow shell reminds us of the climate and pollution catastrophe we’ve created. This genetically engineered creature is a response to the ecological crisis, its shell replaced by an artificial one that features two vacuums to suck up plastics floating in the ocean. ‘Cleaner’ illustrates that while we may be clever at creating technological solutions to climate change, we continue to be the problem.

HOPE is partly a cautionary tale, of how humanity has negatively impacted and reshaped the lives of Earth’s inhabitants and its landscape. But, it also proposes an idealistic posthuman future that seeks a more empathetic relationship with the other, displacing the notion of the superiority of mankind. Piccinini has previously stated that her work attempts to “imagine a different sort of relationship between people and nature; one that is more equitable and with a more shared outlook.” Genetic manipulation and experimentation create a new inter-dependency between species, between the ‘natural’ body and the artificially created body.

We are presented with a vision of a posthuman condition that dissolves the boundaries between male and female, human and animal (or other), human and machine, nature and artificial. HOPE emphasises the need for humanism in technology, and a deeper empathy for animal—and all other—kind.

HOPE at Tai Kwun , 1/F, 3/F JC Contemporary

24 MAY – 3 SEP, 2023

*All photos by the author

You must be logged in to post a comment.