Julie Curtiss 朱莉·柯蒂斯

Hair, both beautiful and abject, ornamental and beastly, is a semiotic system that holds a powerful attraction for French-born, Florida-based artist Julie Curtiss. Born and raised in Paris, Curtiss studied at l’École des Beaux-Arts and then at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Dresden before making her way to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Arguably, the Chicago imagists of her alma mater, like Christina Ramberg – to whose work Curtiss’ is often compared – and her years working as a studio assistant to both Jeff Koons and Brian Donnelly (aka KAWS) have informed Curtiss’ aesthetic, with its vibrant colours, cartoonish figuration and smooth, skilfully rendered lines. It’s a highly stylised visual language that helped her work get noticed on Instagram and reach stratospheric heights of success in the art world. But unlike Kaws’ Happy Meal cartoons and figurines, Curtiss’ work is personal, a deep dive into the female psyche and femininity through Jungian archetypes.

Bitter Apples, Curtiss’ first exhibition at White Cube Hong Kong, brings together works across varied media, including acrylic and oil paintings on canvas, gouache on paper, video and sculpture, drawing from cinema, art history, symbolism and psychology. The artist circles back to themes that have become hallmarks of her work, playing with recurring motifs of femininity and domesticity – faceless portraits that emphasise hair, long, painted fingernails, high heels, cigarettes. “My work is all about domesticated nature and domesticated spaces,” she says, adding in her artist statement: “At the heart of my interest is how nature and culture relate, the balance between our wild side and our domesticated side. And the weirdness of it all.”

Hair, tame and wild – and the women it is attached to – has become a recognisable motif in her oeuvre, in the way it was for Italian surrealist pop art painter Domenico Gnoli. It is both seductive and abject, as well as rooted in the artist’s personal memory. “I remember that single moment when I got interested in hair was when I found my mother’s hair in an old suitcase – it was a long brown braid. I only knew my mother with grey hair. It’s death but it’s also very sensuous when you hold someone’s hair. It’s tactile and it’s part of their body; it’s dead yet it’s alive. It’s a remnant part of her.” Curlicues and rope-like coils of hair are rendered in paint in fetishistic, obsessive detail, flooding her canvases, such as in Nautilus (2023), where an elaborate coiled hairstyle mimics a seashell, and Parrots (2022), with its strands of blond hair framing an ear.

Elements of the sinister or macabre and the absurd creep into Curtiss’ works, creating tension when paired with the whimsical. Earlier works featured beastly, long-clawed hands reaching across the back of a head or holding a cigarette (Conversation, 2016), which call to mind surrealist artist Meret Oppenheim’s Fur Gloves with Wooden Fingers (1936); the top of a head presented on a plate with salad (Food for Thought, 2019); and a hirsute-looking roast fowl (Smoking Turkey, 2016). Khoi Soup (2023), one of two small sculptures in the exhibition, features the head of a red koi carp bobbing in a bowl of soup noodles, looking like it’s just popped up for air, yet likely dead (so one assumes) and served up as food.

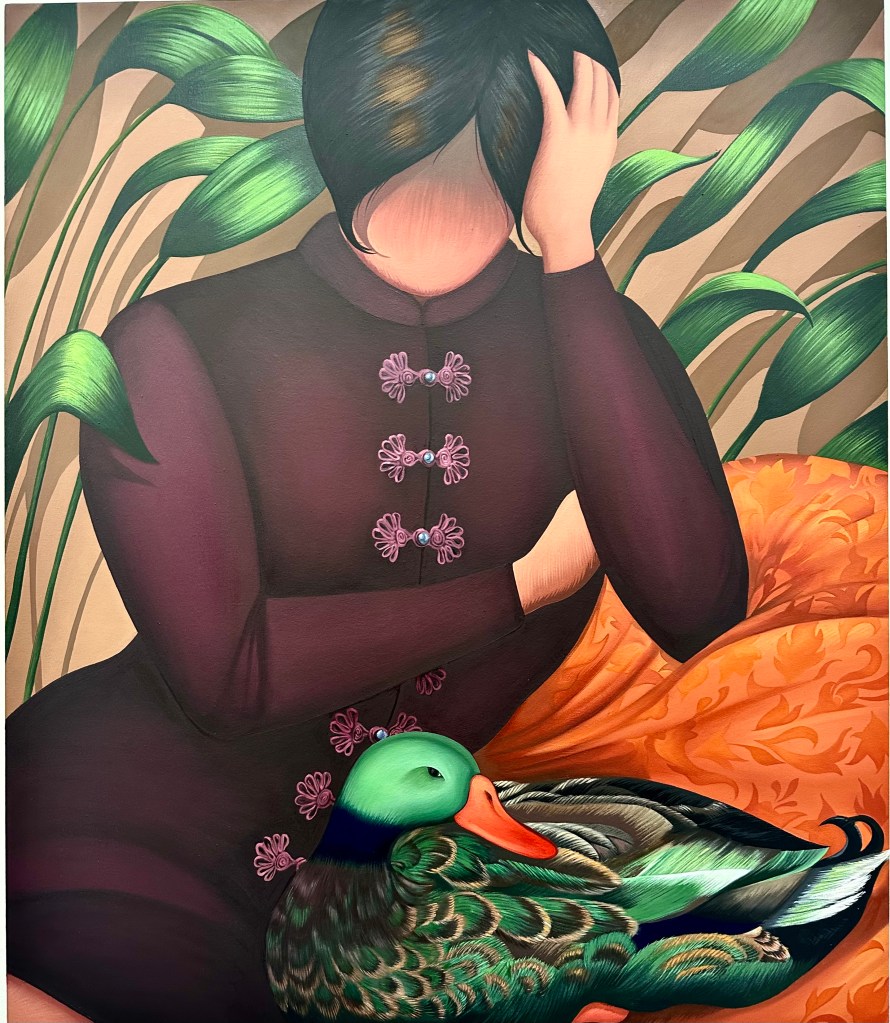

In her portraits, it’s immediately striking that none of the subjects have eyes. Faces are hidden or undefined, like in a dream, creating feelings of unease. Nobody looks back at you from the canvas, inviting, challenging or accepting your gaze. “Because there is this blank face, it is not about one person. It is the idea of people,” the artist explains. In Side Glance (2023), a faceless woman is posed seated on an orange sofa with a green duck against a background of foliage – a juxtaposition of domestic space and nature. In other paintings like Red Umbrella (2023) and South of Eden (2023), all we can see is the backs of her subjects’ heads: their hair. “I don’t want to have characters in my paintings, but I want them to be templates for the viewer’s projection. All I want is to activate the viewer’s narrative,” she says.

The artist’s meticulous, hypnotic linework, painted strand by strand, at times creates the optical illusion of vibration or pulsing, giving rise to an unsettling feeling. Shading and colour blocks are painted with the same hirsute texture made of minute lines, giving the impression that everything is covered in a layer of fur or hair. Even a black umbrella in Under My Umbrella (2022) resembles a head of wet, glossy, raven-coloured hair. This technique alludes to the archetype of a woman with an animalistic drive, calling attention to the interrelation between nature and culture, domesticity and wildness, masculine and feminine, and anima and animus – the Jungian theory describing the unconscious masculine in the female psyche, and the feminine in the male psyche, which informs Curtiss’ work.

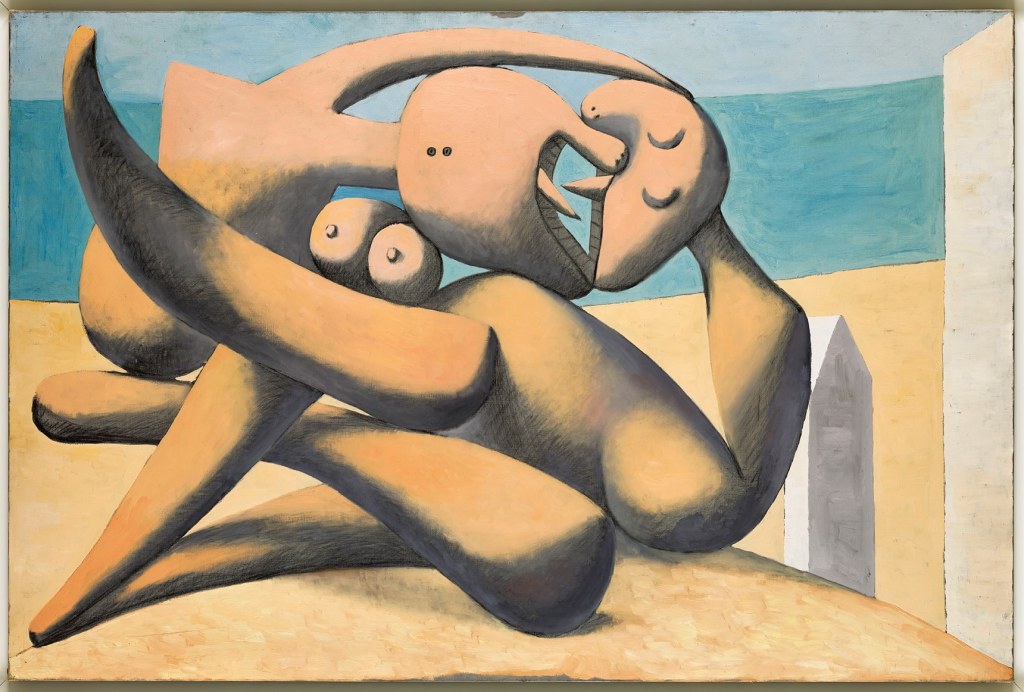

The exhibition is rife with tongue-in-cheek jokes and visual puns. Themes crop up of gender, sexuality, innocence and experience, some within a biblical framework: a large serpent swallows a couple in coitus in Serpent (2023) – an eaten apple, the source of temptation and downfall, appears on a night stand nearby. Employing cinematic language for the compositions of many of her paintings – drawing inspiration from films by experimental surrealist filmmakers like Maya Deren, David Lynch and the noir of Alfred Hitchcock – tight cropping and close-ups of manicured hands, styled hair and body parts encourage the viewer to imagine what is beyond the frame, allowing the unconscious to fill in the gaps and complete the narrative.

In Duel in Eden (2022), the tightly framed image shows the naked torsos of a man and woman, presumably Adam and Eve, facing one another in a fleshy stand-off. The exploration of gender, sex and power is continued in the humorous Duel (2022), in which a cartoonish pair of male and female torsos with genitalia exposed similarly stand before one another, a pistol holster arrayed against a lacey, black suspender belt and stockings, male against female in a battle of the sexes. Rude Clam juxtaposes food and libido, further exploring ideas of pleasure and indulgence. In Horse Chestnut (2023), a gouache-on-paper painting, a pair of woman’s hands hold open a spiky horse chestnut between her legs, while Bolet (2023) depicts a phallic-looking mushroom gripped in a sexually suggestive manner by a woman’s hand.

In the gallery’s upstairs exhibition space, we find a series of works in which nature motifs dominate, arranged in wider angled compositions. Lush, verdant palm trees and tropical birds are juxtaposed with artificial, kitsch domestic spaces. Two large acrylic on oil paintings, Tropical Dawn and Tree of Life (both 2023), feature staged tropical scenes populated with a menagerie of animals like flamingos, crocodiles, rabbits and ibises, invading living rooms. This body of work demonstrates a transition for the artist, reflecting her move to Florida – a paradise both artificial and natural – but also exhibiting more painterly influences, drawing on the history of figurative paintings like those of Henri Rousseau or Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), an Edenic paradise of humans and animals.

Like the surrealists before her, Curtiss enjoys playing with binaries, the juxtaposition of humour and darkness, the uncanny and the mundane, the grotesque painted in vivid colours, and exploring the fine line between abject and the attractive, thanatos and eros. Bitter Apples brings this all together in a delightful, subversive, colour-saturated joyride. Ultimately, Curtiss says, her work is a reflection on chaos and order, “a consideration of systems and things that are misplaced. It’s about the throwing of a wrench into a perfect system.”

Published on Artomity, October 30, 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment.