Long after her male counterparts like Man Ray and Max Ernst came to attention, American photographer, Lee Miller, like many overlooked women artists throughout history, is finally getting the institutional and market recognition she deserves.

Recently there have been three noteworthy exhibitions of Miller’s photography—Seeing Is Believing: Lee Miller and Friends at Gagosian in New York City, You Will Not Lunch In Charlotte Street Today at TJ Boulting in London (through January 20th), and Surrealist: Lee Miller at Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne (through February 25th), as well as a recently released biopic Lee, starring Kate Winslet and adapted from her son, Anthony Penrose’s book The Lives of Lee Miller (1985).

The Heide exhibition features 100 of Miller’s photos taken from the late 1920s to the mid-1940s, just barely enough to give us an insight into the many lives of this extraordinary and complex woman and photographer. Despite the title of the show, the exhibition encompasses diverse genres that demonstrates Miller’s talent and relevance beyond Surrealism, including fashion photography, commercial studio work, portraits, travel, and Miller’s work as a war correspondent in the Second World War.

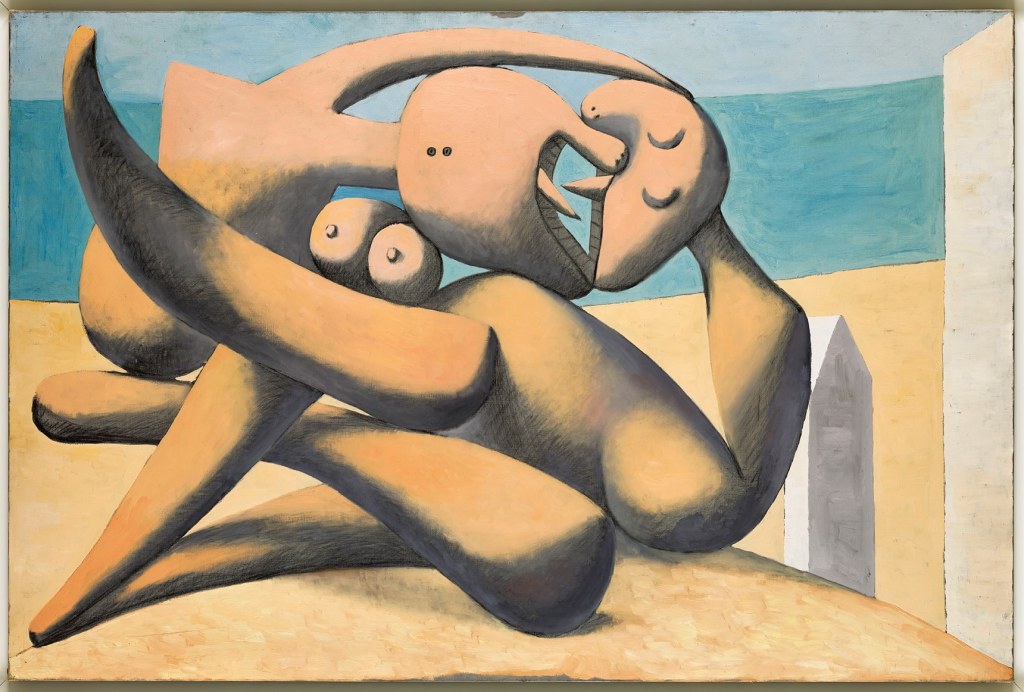

Born in New York State in 1907, Miller was a Vogue cover model in the United States, then a Surrealist photographer in Paris, where she took her first photographs in the streets and Man Ray’s studio in 1929. Despite all of this, her contributions throughout history have often been reduced to that of muse— Picasso painted her six times, and she was the collaborator, lover and ‘muse’ to surrealist photographer Man Ray.

However, her three-year relationship with Man Ray was an artistic dialogue in which both creatively influenced the other. This blurriness of attribution is illustrated in the exhibition which includes works that were a combination of Man Ray’s and Miller’s ideas, such as the 1930 photograph of Miller’s neck, and a photograph of a woman’s head under a bell jar (‘Tanja Ramm under a Bell Jar’, Paris, 1931).

Amongst the curated selection numerous photographs rise above the prosaic of perfume bottles and street photographs, like the abstracted nude torso in ‘Nude Bent Forward’, 1930, all sinuous curves with a masterful play of light and shadow, resembling a perfect classical marble sculpture. Miller herself makes a beguiling subject in her own self-portraits— both authoress and her own muse—like in her flawlessly lit side profile of ‘Self Portrait’, New York Studio, New York, USA, 1932, resembling an idealized pre-Raphaelite beauty.

It is clear from the exhibition that Miller developed her own idiomatic language separate from her artistic milieu, which included Picasso, Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau and her husband, Roland Penrose. She displays the Surrealist penchant for juxtaposing subjects to produce startling combinations, but does so not through photo manipulation or collage, but through careful composition and close cropping, and an eye for the amusing, absurd, and unconventional, searching out the extraordinary in the ordinary. For example, a woman’s hand reaches out for a door handle, partially obscured by the scratches on the glass pane so that the hand looks shattered in ‘Untitled (Exploding Hand)’, Paris, France 1930.

In ‘Man and Tar’, Paris, 1930, melted tar stretches out like manta ray fins towards a pair of men’s shoe-shod feet. While in ‘Fire Masks’, London, 1941, we see two beautiful models wearing metal face covering masks in the London blitz, looking over their shoulder at the camera, blurring the boundaries between art photography and photojournalism. The ruins of wartime London and Paris became the backdrop for high-fashion shoots.

Miller asserted herself against the grain of the Surrealist practice of objectifying women’s bodies with ‘Untitled (Severed breast from radical surgery in a place setting)’, Paris, 1929. During a commission in a hospital she came upon a severed breast, arranged it on a table like a meal and photographed it, a dark yet tongue-in-cheek commentary on the erotic fetishization and visual fragmentation of women’s bodies in Surrealist art.

But perhaps Miller’s most memorable and affecting work wasn’t her Surreal works, but her Vogue commission as a photojournalist during the Second World War—partnered with a male co-photographer, David E. Scherman, a photographer for Life magazine. She was among the first photographers, and the first woman at that, to unsparingly document the horrors and liberation of the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald, the latter of which were published in June 1945, along with her own accompanying text, in British and American editions of Vogue.

With Scherman Miller visited Hitler’s home in Munich, where the controversial image of Miller bathing in Hitler’s bathtub was taken, the bathmat muddied with the dirt of Dachau from her boots—the reality and horrors of Nazi persecution dragged through the Führer’s private space. “I washed the dirt of Dachau concentration camp off in Hitler’s own tub in Munich,” Miller reported in a radio interview. Unbeknownst to the pair, the photo was taken on the very same day, 30 April 1945, Hitler and Eva Braun died by suicide in their Berlin bunker.

This image deconstructs the Hitler myth; in the small, average-looking, tiled bathroom, a portrait of Hitler is perched on the bathtub ledge, his gaze towards Miller as she bathes, while on a table beside the bathtub stands a small, kitsch, classical statue of a nude. Miller highlights the ordinariness that lay hidden behind the Hitler myth, with its petite bourgeois taste, and juxtaposes this frivolity with the horror of the concentration camps— the boots caked with the mud of Dachau—exposing what Hannah Arendt described as the banality of evil, or in this case, the banality behind evil, the routinised ordinariness that lay behind acts of horror and brutality.

Alongside this image hang a handful of photos documenting the liberation of the Nazi death camps including a photograph of a pile of emaciated, dead bodies in the courtyard of the crematorium in Buchenwald (‘US Soldiers Who Are Used to Battle Casualties Lying in Ditches for Weeks Are Sick and Miserable at What They See…’, Buchenwald, 1945). Even in an era in which graphic war photographs and trauma porn have become ubiquitous on social media, this image never fails to shock and deliver a visceral punch to the gut. The frontal photograph of the horrific scene is taken close enough that the viewer can make out the facial expressions of the prisoners—mouths agape, heads shaven— and skeletal limbs reaching out towards the lens. A row of prisoners in their striped uniforms stand behind the pile of bodies, each looking on at the indescribable.

Beside this are photographs of dead and beaten Nazi officers such as ‘Dead SS Guard, Floating in Canal’, Dachau, Germany, 1945, in which a dead prison guard floats in the current of the canal, framed by long grass, like some macabre, fascistic Ophelia— a scene both gruesome yet also perversely beautiful. These images push the boundaries of war photography, and are a stark contrast to her earlier fashion photography and social documentary photographs, but this exhibition is full of visual contrasts, and none more so than in this particular room, where victims and perpetrators are arranged side by side. They are hard to look at, but even if you were to peel your eyes away quickly, they are seared into your memory.

Whether capturing the glamour of fashion, the carefree bohemianism of her social circle or the destruction and cruelty of war, Surrealist: Lee Miller, is testament to trailblazing Miller’s scope and output as a photographer, but also her defiance and courage in life and art.

You must be logged in to post a comment.