He was one of the most original filmmakers of our time. Delving into the post-ism archives, we revisit a 2009 interview with filmmaker David Lynch to discuss his exhibition of paintings at Griffin Gallery, Santa Monica.

It is almost dawn in Hong Kong and a wind is whipping the windows and just starting to howl in frenzy, presaging a typhoon, when I hear David Lynch’s slightly nasal, sunny voice over the phone from Los Angeles. My two recently rescued feral cats hiss and scratch from the shadows, shaking a houseplant so that it looks like it’s taken on a life of its own, and interrupting the quiet domesticity of my environs. I suppose you could call the scene Lynchian.

The man who over the years has earned his own adjective in the common vernacular to describe the disturbing and weird, juxtaposed with the mundane, David Lynch is often cited as one of the most original filmmakers of our time. He’s received Academy Award nominations for his films The Elephant Man (1980), Blue Velvet (1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001), and won France’s César Award for Best Foreign Film, the Palme d’Or, and the prestigious Golden Lion award for lifetime achievement at the Venice Film Festival. As a director, Lynch has confused, seduced and shocked audiences, attracting in the process a huge cult following and influencing a generation of image makers.

you have to stay true to the idea and translate it so that every element feels correct.

But although his name is synonymous with it, film is by no means Lynch’s only passion or accomplishment. He is also a prolific visual artist, with an upcoming exclusive three-month show at the Griffin Gallery in Santa Monica. Titled David Lynch: New Paintings, this exhibition of 13 mixed-media paintings is far from Lynch’s first. He has previously exhibited work over the years in Paris, Moscow, Barcelona, Spain and Italy, and is represented by major art dealers around the world, including James Corcoran in Los Angeles, and Leo Castelli in New York. In 2007 the Fondation Cartier pour l’Art Contemporain in Paris curated a show of Lynch’s artwork spanning over 40 years. Recently, a collaborative effort with designer Christian Louboutin on a photographic exhibition, toured internationally, bringing a dreamlike, sensual, neo-noir aesthetic to galleries the world over. Like his films, his artworks are equally divisive with audiences: some find his works disturbing and slightly confusing, whereas others laud them as inspirational and genius. They are all of this and more.

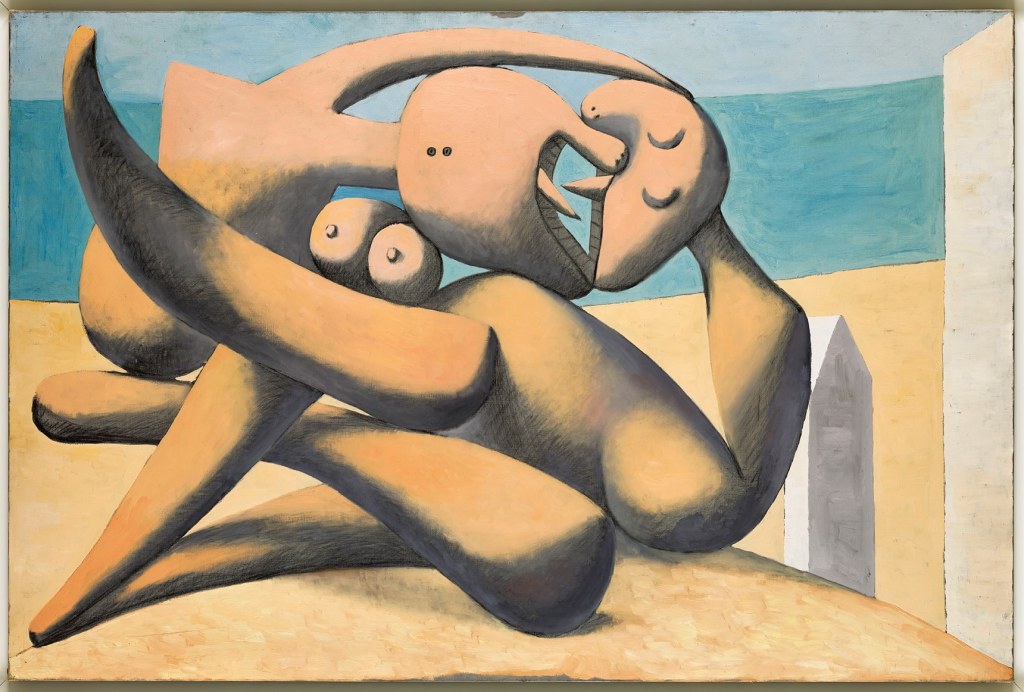

Inspired by artists like British figurative painter Francis Bacon and Austrian expressionist, Oskar Kokoschka, Lynch has always been drawn to painting and photography. In fact, David Lynch the filmmaker was initially David Lynch the painter. “I wanted to be a painter since I was in the 9th grade”, he explains. Attending the Boston Museum School for a year and then the Pennsylvania Academy of Art, it was at the latter in 1966 that Lynch first made short abstract films, or “moving paintings” as he once referred to them. “Film combines all the arts, but painting is such a beautiful world in itself and I’m in love with the world of painting,” the artist and filmmaker says.

Lynch’s paintings, photographs, and drawings capture an unfettered imagination run wild, drawing from his childhood experiences, his adolescent fantasies, and his adult preoccupations. Scenes of home and suburbia, complete with its potentially sinister underbelly, repeatedly surface in his oeuvre, alongside Lynch’s signature dark sense of humour, echoing the off-kilter comic relief found in even his most disturbing film work.

The artist doesn’t have to suffer to express suffering. If you get ideas that you want to translate to a medium you will derive so much more enjoyment from creating.

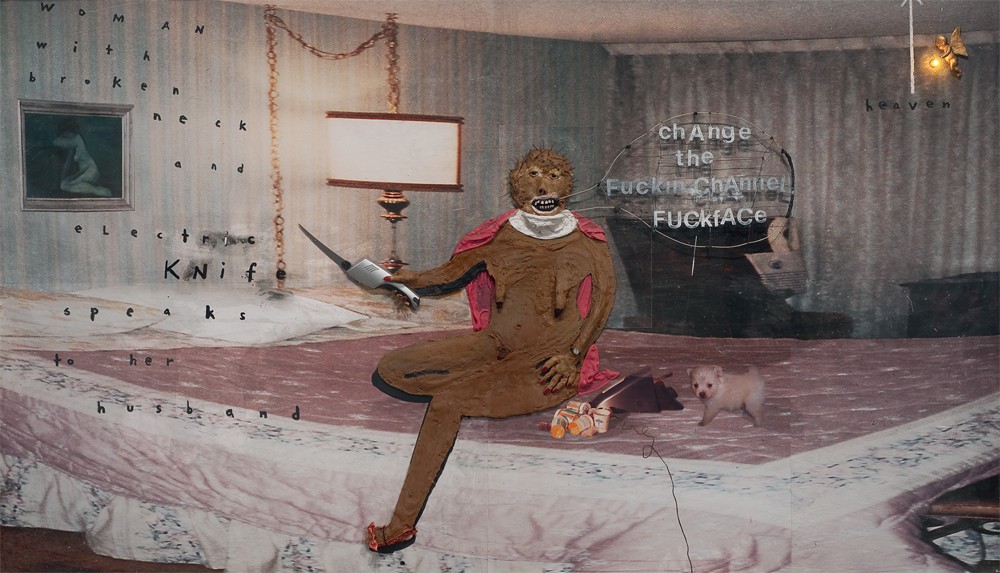

As in his films, Lynch’s surreal, mixed-media paintings evoke a sense of the uncanny or bizarre. There is also an intimation of violence bubbling beneath the surface, or behind the curtained windows, of the perfectly cultivated, middle-American, suburban veneer, as in ‘Change the Fuckin’ Channel Fuckface’ (2008–09, 72 x 120 inches). In this large mixed-media work we see a monstrous-looking, leather-skinned, nude female figure wearing a red cape and a neck brace, and wielding an electric carving knife. Sitting beside her on a pink bed spread is a tiny, collaged, Pomeranian dog, while a speech bubble featuring the title is spelled out in typeface suggestive of a ransom note. Across the left side of the canvas we read, as though stage directions in a script, ‘Woman with broken neck and electric knife speaks to her husband’, scrawled in black letters.

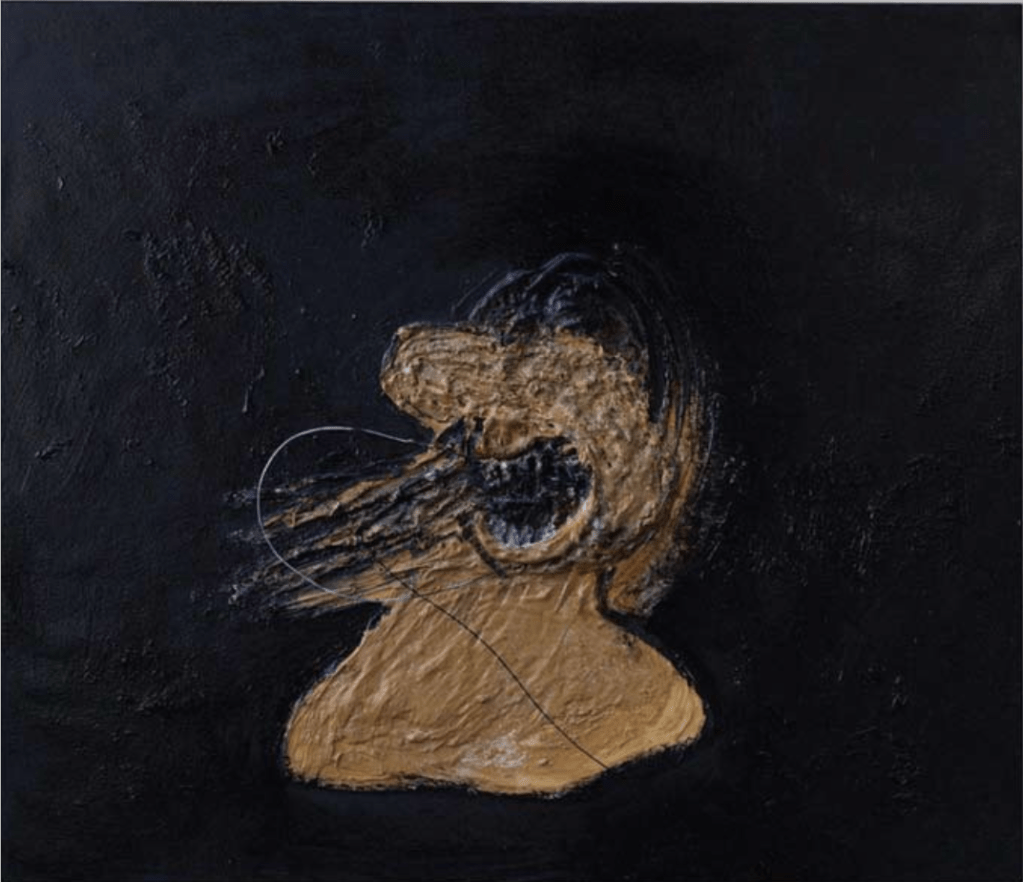

Many of Lynch’s figurative paintings have an organic, sculptural quality to them. Built up with layers and thick blobs of paint, or collaged with other mixed media, his misshapen painted figures give the impression that they are trying to push their way through the flat canvas surface and into the third dimension. “I like three dimensions for some reason,” he states. “I’m not in love with the flat surface anymore so my paintings are borne out of that feeling. I like organic phenomena.”

The painting ‘Figure #2 Man Laughing’ (2009), depicts a heavily impastoed and distorted figure — only a gaping, toothy, mouth is discernible— emerging from a flat, black-painted background. Evocative of a Francis Bacon portrait, the work simultaneously conjures up the motif of transformation or dual personalities and doppelgängers of characters in Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive. The three-panel mixed-media on cardboard painting, ‘Pete Goes to His Girlfriend’s House’ (2009) shares a similar tactile and sculptural quality. Here we see a menacing, long-limbed, gun and knife-wielding figure—weapons and arms rendered three-dimensional— scampering across the board towards a screaming woman. Three small, red lights glow like embers above his head.

Unifying the selection of paintings in the exhibition is a sense of creeping darkness, both literal and figurative, countered by a childlike, naïve quality. “Yes”, the artist and filmmaker laughs. “It’s childlike and it’s pretty bad painting. You know this child thing is for me where it’s at. I love absurdity because I see so much of it in the world. I love the humour in it.” Like his films, Lynch’s paintings remind me of the works of Austrian-Czech writer Franz Kafka, with their ability to incisively probe the darkest corners of the human condition while simultaneously highlighting the absurdity of it. “I guess painting is based on the human condition,” he muses. When asked how he feels about his work chronically getting referred to as disturbing Lynch explains, “That’s a common misunderstanding. There are plenty of disturbing things in my films, and possibly in my paintings, but there are other things swimming in there that some people pick up on. When you stand in front of a painting, I always say a circle is created: the painting goes into you and it goes through your mind and your emotions. Each viewer is going to have a different experience.”

Film and painting share not only thematic commonalities, but also a similar creative process for Lynch. “Films are like paintings, it all starts with an idea. The films are based on ideas that come in a script form and although painting is built more on action and reaction, it’s still a flow of ideas, just in a world of paint.” One, however, is seemingly more collaborative and the other solitary and intimate? I ask. “Filmmaking actually is not really a collaborative process,” he counters. “If it was it would be a mess. It’s exactly the same as painting but in filmmaking you have a hundred people around you. But you have to stay true to the idea and translate it so that every element feels correct.”

This creative process is nourished by his 36-year practice of transcendental meditation. In July 2005, he launched the David Lynch Foundation For Consciousness-Based Education and Peace in order to help finance scholarships for students in high schools who are interested in learning the transcendental meditation technique, and to fund research on its effects on learning. It is a subject for which he has boundless passion and knowledge, speaking as one who has been profoundly changed by his discovery of it.

“Transcendental meditation is a mental technique, an ancient form of meditation that allows any human being to unfold and realise their full potential, and a state of enlightenment. You transcend into a fuller, purer, brighter consciousness which manifests in infinite creativity, love and peace. And it’s there for the human being. When you start expanding that consciousness you can connect to your ideas on a deeper level, you have more happiness in your work. Your understanding grows and the world looks better because you’re understanding this consciousness. Anger, fear, depression, stress and sorrow…these things start to slide away and you experience so much more freedom in your work.” This disclosure seems incongruous with Lynch’s work which often revels in abject horrors. But Lynch adds, “Art for me is translating ideas in the world of paint. These paintings come from ideas conjured from our world. The artist doesn’t have to suffer to express suffering. If you get ideas that you want to translate to a medium you will derive so much more enjoyment from creating.”

When you start expanding that consciousness you can connect to your ideas on a deeper level, you have more happiness in your work, your understanding grows…

Lynch’s four-decade career has encompassed a phenomenally influential artistic output across multiple media, characterized by numerous creative risks taken, and a unique, singular vision that is unmistakably, well, Lynchian. But the creative polymath has no intention of hanging up his director’s clapboard any time soon. “I love both things, film and painting. And I love still photography and music, so, I think I can move from one medium to another depending on the ideas forming at the time. I do love the world of paint and hope to keep on painting.” Exchanging our goodbyes, Lynch gets back to his coffee—one of 20 he drinks throughout the day— and to creating worlds of noir-beauty and horror that will no doubt weave themselves into our psyche, and leave an indelible mark on contemporary culture.

First published in Peninsula Magazine, 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.