A cursive neon sign reading Sex and Solitude (2025), the title of British artist Tracey Emin’s exhibition, glows in blue above the arched stone entrance of Florence’s 15th-century Palazzo Strozzi, its modern light starkly contrasting with the building’s ancient sand-coloured façade. As visitors step into the expansive courtyard of this historic square building, they encounter I Followed You to the End (2024), a monumental bronze sculpture. At first glance, the piece appears abstract, but a closer look reveals the figure of a nude woman in a kneeling, all-fours position. Her posture, with prominently raised buttocks, directs the viewer’s gaze inescapably toward this aspect of the work as they move around it. The female body and eroticism occupy the space traditionally reserved for heroic male bronze sculptures, bringing the intimate and female sexuality boldly and confrontationally into the public realm.

The British artist’s inaugural institutional exhibition (16 March to 20 July 2025) in Italy showcases 60 works spanning four decades of her career, charting Emin’s autobiographical journey while engaging in dialogue with the renaissance tradition and architecture of the Palazzo Strozzi. Curated by Arturo Galansino, Director General of Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, this deeply personal exhibition features paintings, sculptures, needlework, appliqué, video, and neon art that explore the artist’s emotions and experiences, from tender to brutal, with unwavering honesty.

Emin’s art has always been confessional and raw. While her male YBA counterparts made their mark with playful provocation, from multicoloured spot paintings, pickled sharks, and doodled penises over Hitler’s banal watercolours, Emin blazed onto the scene with uninhibited sexuality and unapologetic honesty making her lived experience the core of her practice. Her work explored deeply painful personal experiences—abortion, rape, teenage sex, abuse, and poverty—bringing to the fore subjects that stood in stark opposition to the YBAs’ irreverent cynicism and provocations, and provided ample fodder for mainstream media and commentators alike.

Emin channels her reflections on longing, desire, pain, and suffering into raw, emotionally charged visual narratives that resonate universally.

Although her work was often labelled controversial and she was painted as an enfant terrible, Emin has always approached her art with sincerity, even if she was at times thumbing her nose at the establishment. Take, for example, her infamous installation Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963–1995: a tent embroidered with the names of everyone she had shared a bed with—lovers, friends, relatives, even her grandmother—between 1963 and 1995. The piece polarized critics and audiences; some dismissed it as blatant sexual exhibitionism for exposing what is typically private. However, this interpretation missed the artwork’s intent. Rather than simply courting shock value, Emin’s piece opened up a conversation about the complexities of intimacy and human relationships, underscoring how simply sharing a bed with someone transcends mere sexuality. At the time, it was a groundbreaking, radical work that challenged the boundaries between private and public life. The tent was destroyed in a 2004 fire and thus not included in the exhibition, but the works on view in Sex and Solitude continue to break taboos about the female body and sexuality, and blur the boundaries between private and public.

The exhibition title, Sex and Solitude, captures two fundamental forces in Emin’s life and art: on one side, sex—with its ties to her wild youth, intimate relationships, desire, and the wellspring of inspiration behind much of her work; and on the other, solitude—not just as an essential condition for artistic creation, but, for Emin, as something entwined with experiences of illness. At Palazzo Strozzi, Emin channels her reflections on longing, desire, pain, and suffering into raw, emotionally charged visual narratives that resonate universally.

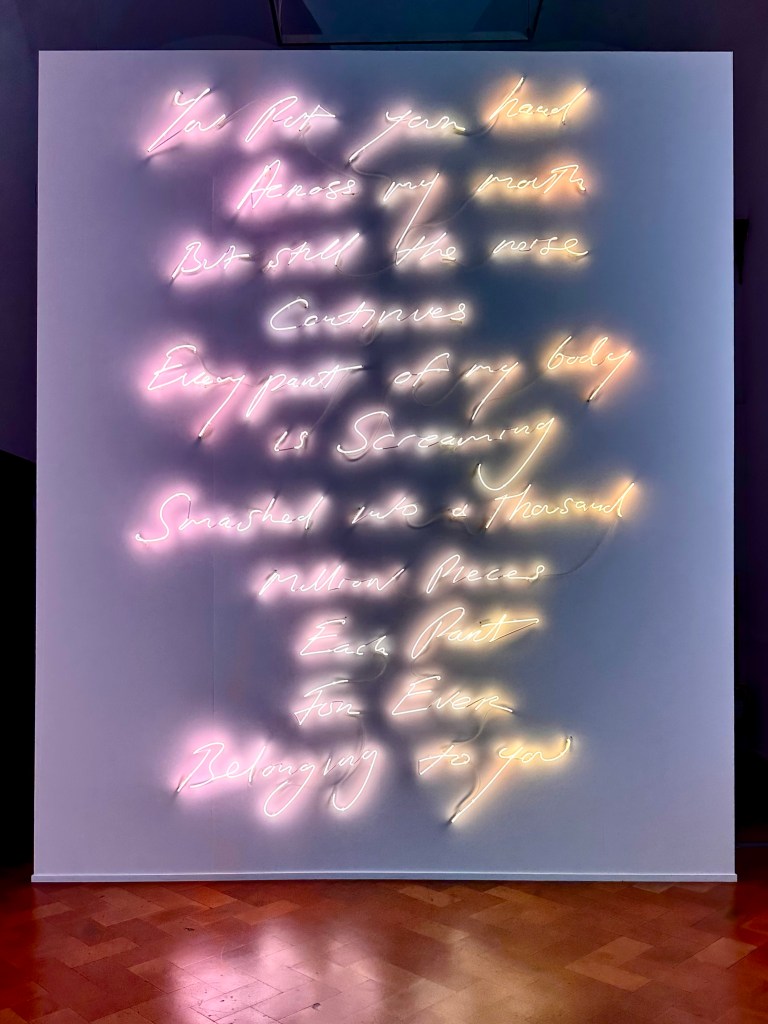

In the first exhibition room, Love Poem for CF (2007) — a towering neon sculpture standing over four metres tall— bathes the space in a soft pink glow. The glowing script draws from a poem Emin wrote in the 1990s for her ex-boyfriend Carl Freedman, encapsulating themes of heartbreak and yearning. Emin’s use of neon evokes the nostalgia of her childhood in Margate, with its seaside amusement parks, while also referencing the medium’s traditional associations with commercial signage, nightlife, kitsch, and seduction. However, she subverts these connotations by transforming neon into a vehicle for raw, autobiographical and poetic expression. In doing so, Emin turns intimate emotion into public spectacle, preserving fleeting feelings of desire and vulnerability in electric permanence.

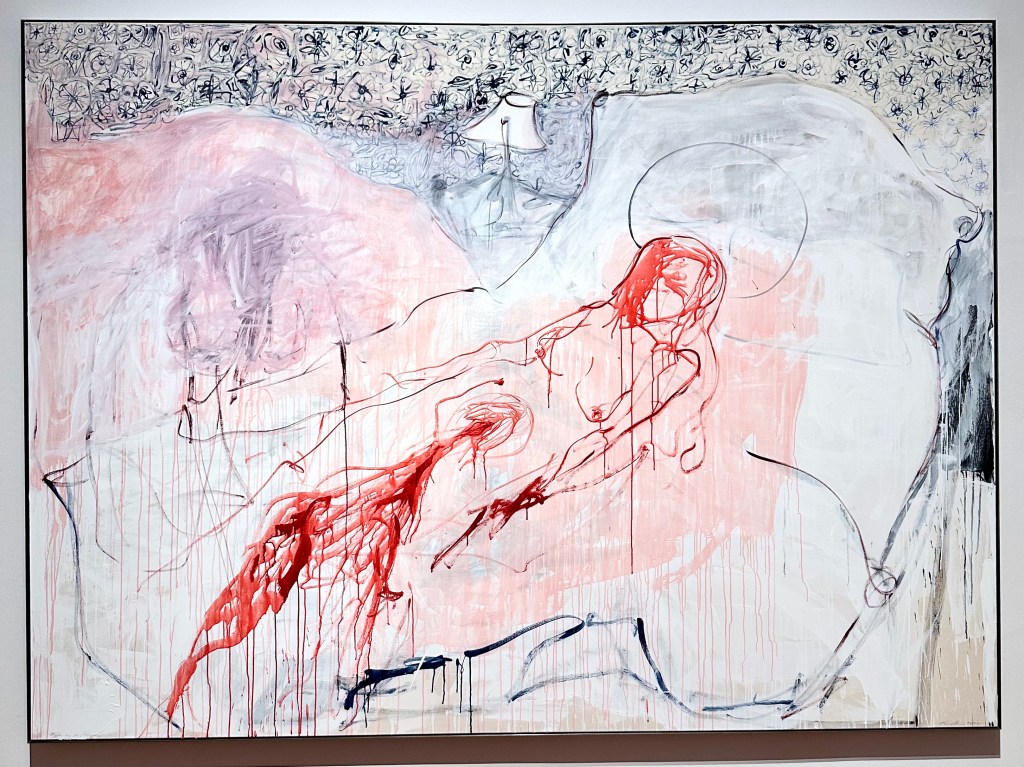

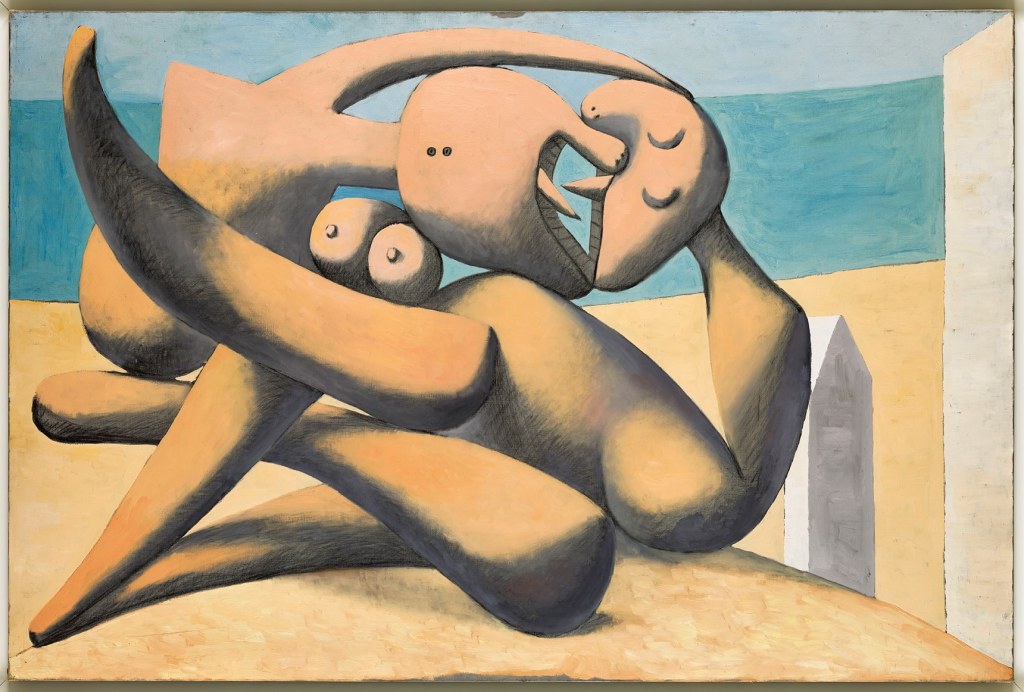

Flanking the neon installation are two large canvases: There Was No Right Way (2022) and Everything is moving nothing Feels Safe, You made me Feel like This (2018). Both paintings depict gestural, abstracted figures entangled and twisted together, their bodies emerging from energetic, chaotic brushwork and overlapping washes of rich reds, pinks, whites, and blacks. These figures seem to surface from—and simultaneously dissolve into—the vibrant compositions. The visual approach recalls the influence of Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele, whom Emin cites as inspiration. Like Schiele, Emin’s paintings pulse with emotional intensity and psychological tension, immersing viewers into her emotional landscape through furiously painted gestural brushwork and frantic outlines that form desperate tangles of bodies. These expressive marks convey raw vulnerability and turbulence, allowing the physicality of paint to mirror the intensity of the feelings and experiences she channels into her work.

In 2020 Emin was diagnosed with an aggressive form of bladder cancer and underwent extensive surgery, including the removal of her bladder, uterus, cervix, part of her bowels, and half of her vagina. While that year was one of solitude for many of us around the world as we experienced Covid lockdowns, for Emin it was life altering. Numerous works featured in the exhibition make reference to the surgery, and subsequent recovery, that reshaped her life, body and art, touching on themes of survival, mortality, and desire. There was blood (2022) a large painting which was featured in Emin’s Lovers Grave exhibition at White Cube (New York, 2023–2024), depicts the black outlines of a couple embracing on a bed awash in intensely saturated crimson the colour of blood, while red paint drips and pools vertically down the canvas like a curtain, suggesting violence, death and suffering but also life, love and intimacy. It is a painting of desire and passion even in the midst of pain and physical trauma.

The work pulses with urgency, born from Emin’s confrontation with mortality, and a palpable sense of dislocation from her own physical self.

After undergoing invasive surgery, Tracey Emin was left with a stoma—an element of her post-operative body that she sometimes incorporates into her artwork. Her candid engagement with it underscores both life’s fragility and the fierce will to survive. In a film screened as part of her 2024 White Cube Bermondsey exhibition I Followed You to the End, Emin reflects: “When you have a stoma, sometimes it bleeds… My stoma keeps me alive, keeps me here, this blood that is flowing is my blood and it’s mine.” This raw acknowledgement of her altered body is part of a broader artistic exploration of illness, survival, and transformation.

These themes are powerfully expressed in Not Fuckable (2024), a work that confronts the realities of illness, aging, and recovery. Here, Emin grapples with the physical and emotional aftermath of cancer surgery, confronting the viewer with a body rendered both as object and subject—vulnerable, yet unyielding. The work pulses with urgency, born from Emin’s confrontation with mortality, and a palpable sense of dislocation from her own physical self. The result is a luminous tension: a body marked by loss, yet asserting its continued presence.

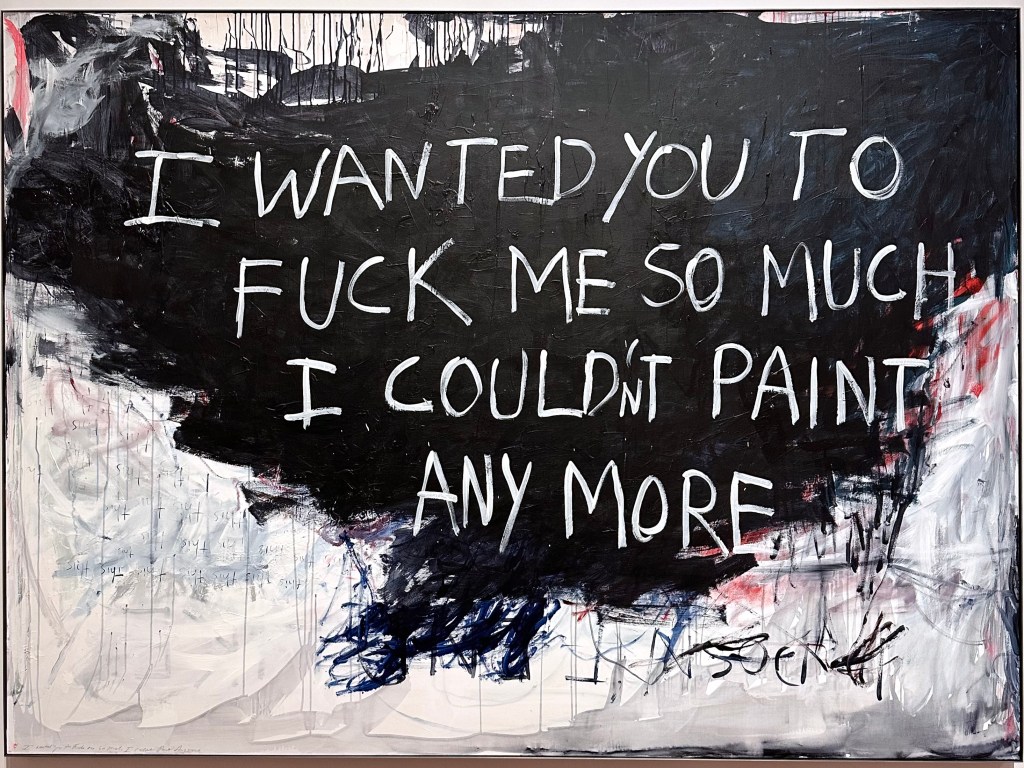

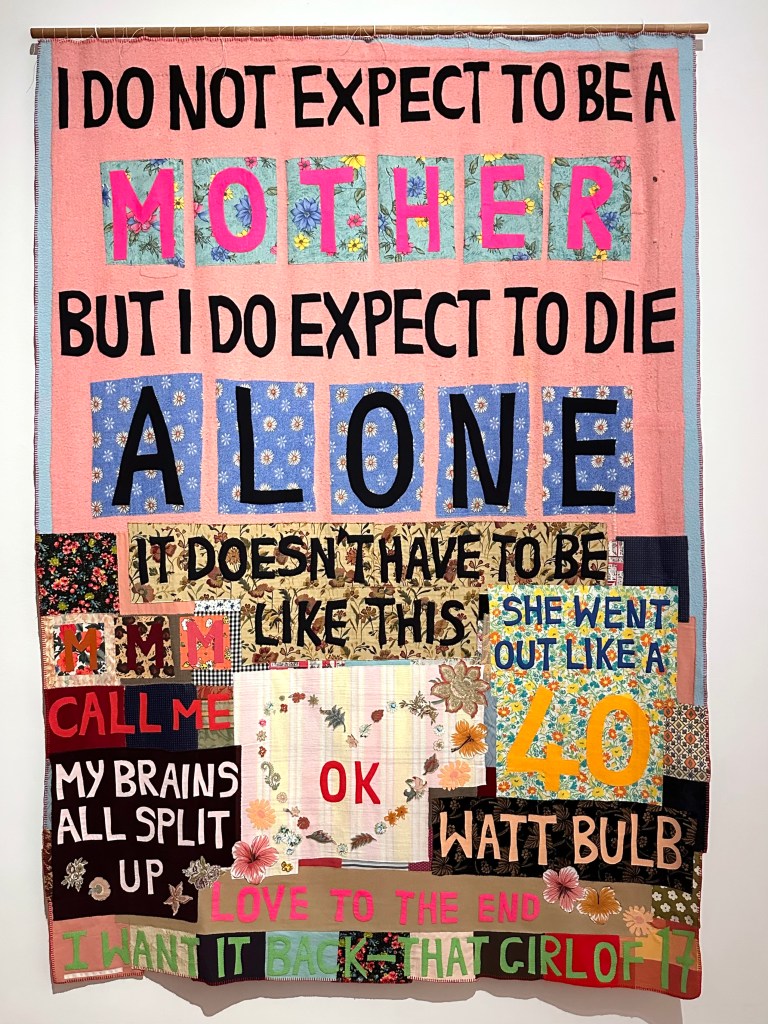

Emin’s titles, like her works, are deeply autobiographical—rooted in personal memory, emotion, and lived experience. They often serve as the genesis of new creations, setting a tone of confession and catharsis. Her signature use of handwritten text—whether culled from diaries, private notes, or spontaneous emotion—recurs across media, from her iconic neon light installations to paintings and embroidered textiles.

I Wanted You To Fuck Me So Much I Couldn’t Paint Anymore (2022) is painted in white capital letters against a black mass of scribble. A large textile piece I do not expect (2002) features stitched phrases like “I don’t expect to be a mother but I do expect to die alone,” conveying Emin’s reflections on motherhood, mortality, and solitude. Using a traditionally ‘female’ craft, the work communicates a message that challenges conventional notions of womanhood, and compels viewers to engage with often-unspoken dimensions of female experience.

Together, the works in this exhibition testify to Emin’s extraordinary resilience—personally and artistically. They illuminate the raw immediacy of survival, loss, desire, and the aching persistence, and joy, of life itself.

You must be logged in to post a comment.